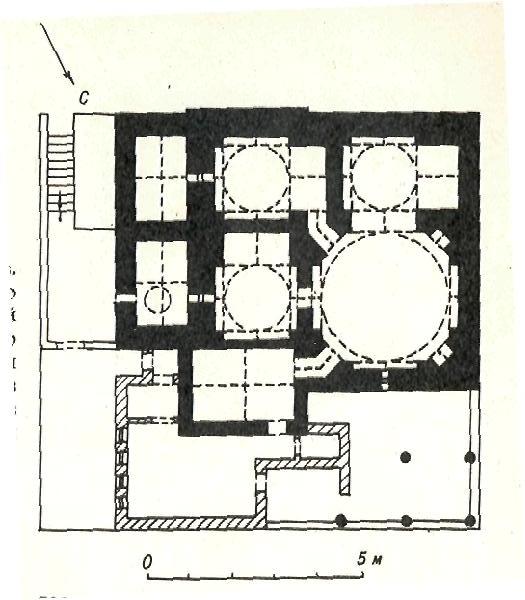

The Eastern Bathhouse is located 80 meters southwest of the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi and is partially under the ground. The monument is of republican significance. Coordinates: 43˚17.787΄, 068˚16.331΄. According to archaeological research, the bathhouse was built in the 1580s–1590s during the reign of Abdullah Khan and was intended for the numerous pilgrims visiting the mausoleum. The overall dimensions of the structure are 17 x 15 m, with a height of 4.8 m. All bricks used in the construction measure 25 x 25 x 5 cm. Until 1975, the bathhouse continued to serve its original purpose for the local population. The structure is semi-underground, built of fired brick, and covered with five domes. It comprises nine rooms that, at different times, served various functions: washing halls, rooms with hot and cold water, massage rooms, and other service areas. In 1979, the Eastern Bathhouse was converted into a museum in order to preserve this outstanding monument of medieval architectural art for future generations. In general, many scholars of the East between the 10th and 16th centuries, such as Rudaki, Nasir Khusraw, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), al-Maqdisi, Ibn Fadlan, Narshakhi, Ibn Battuta, Babur, Wasifi and others wrote about Eastern bathhouses and their design.

Archaeological excavations in many medieval cities of Kazakhstan have uncovered remains of bath complexes. For example, in Otrar were found three bathhouses dating to the 9th–15th centuries; in Taraz two bathhouses from the 9th–12th centuries; in Sauran — a 15th-century bathhouse known as “muricha”; in Turkistan, a bathhouse was studied that represented an enlarged and more advanced version of the “muricha”. Similar traces of bath complexes were found in the ancient cities of Kayalyk, Saraishyk, Aktobe-Balasaghun, and Zhaiyk (Shagan).

Medieval bathhouses were generally divided into two main types. The most widespread type, intended for townspeople and pilgrims, was the “Hammam”. The architectural arrangement of hammams and the number of rooms varied widely. The Turkistan bathhouse represents an advanced and highly developed form of the hammam, with a well-designed system of rooms and heating technology. In a fully developed bathhouse, there was usually a prayer space “mihrab” on the qibla side. In this case, however, the massage room served this role. Next to it was the cold-water chamber “khunukkhana”, which could also be used for prayer. Special niches called “mustahabkhana” were designed for ablutions before prayer — for washing, shaving, and purification. In the Turkistan bathhouse, such niches were screened with woven reed curtains (shypta). The “taharatkhana” — a room for washing feet, hands, and face was replaced here by the hot-water chamber “gharmkhana”.

The visitors would first enter the “chomakhana” (changing room), where they undressed. Next to it was another room with a heated floor, where visitors, having tied a special apron – “lungi” – around their waist, sat for a while, getting used to the heat and then moved into the octagonal central washing hall “miyan saray”. Here, in the large octagonal bath located in the middle, they warmed up and steamed. The visitors would then enter the hot steam room “gharmkhana”, where they thoroughly warmed up, before pouring hot water from a special ladle, the “taz”, and headed to the cold chamber “khunukkhana”, where, at a special corner called “sarshui”, they mixed hot and cold water, lathered themselves completely, and rinsed off the foam with warm water. This process was repeated several times, after which visitors would go to the resting area “chaikhos”, where tea was served. In our case, this function performed in the entrance hall in winter and under the open, canopied veranda in summer. Here, on wooden benches, people, covered with robes, drank tea, smoked water pipes “korkor”, used “nasyvai”, and had conversations. At that time, the eastern the bathhouse was regarded as a place of social gathering where city news, market prices, official decrees, and rumors were shared. Visiting the bathhouse every other day became common and was even mentioned in the bathhouse rules written in the 11th century. The complex also included the “chokhana” with a well supplying cold water, an underground chamber with a fireplace “gulkhan”, and a wood storage area. Such a full bathhouse complex was called “hammami mukhtasar”. They were typically built inside the main city gates through which caravans passed, often accompanied by caravanserais, small mosques, and market stalls on adjacent squares “maidan”.

The buildings were usually half-underground to preserve heat, with only the domes visible above ground. These hammams typically had separate sections for men and women, but more often operated alternately: one day for men, the next for women.

The second type of bath resembled modern shower facilities. In these, an attendant on the upper floor poured warm water down through a pipe. These smaller baths, also made of fired brick, were built inside deep excavated pits, with heated floors and walls connected to a flue system. They were called “muricha” and were usually constructed in the courtyards of neighborhood mosques, serving primarily local residents as well as travelers. Since homes typically had only 2–3 rooms, praying at home was considered improper (nas), so Muslims performed ablutions in mosque bathhouses before prayer. In the “muricha”, visitors undressed in a special room, then entered the washing chamber. By knocking on the water pipe protruding from the wall, they signaled the water attendant (Kadym). Each person was entitled to three pouring of warm water from a 4–5 liter gourd vessel called “dastkada”: the first to wash off dust, the second after soaping, and the third to rinse off. Sometimes was used yogurt for hair care. These bathhouses were usually entirely construccted underground, with only chimneys visible above. Public “muricha” were intended exclusively for men. Each had its own well, or if not, a special domed reservoir “sardoba” lined with waterproof plaster “kyr” for storing cold water. A separate wood store was also present.

According to medieval sources, the city of Balkh had more than 500 “muricha”, alongside large hammams; in Bukhara had more than 200. In 1833, traveler P. I. Demaison wrote that there were 50 large hammams in the city. In Turkistan, records from 1911 note 41 mosques, some of which had “muricha” bathhouses. Between 2019 and 2023, archaeological excavations in the shahristan of the city uncovered the remains of a large “muricha”.